My father knew his knots and splices, and

how to wind a hose in even loops without a kink.

These were skills he learned in boot camp, before

shipping out across the often fatal seas. Now,

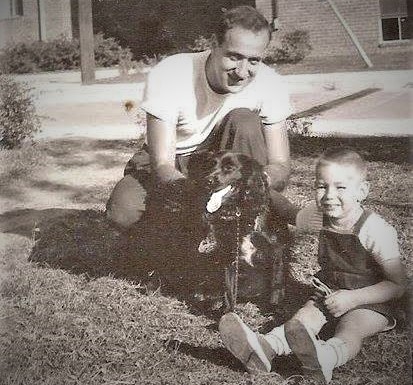

with a house, a car, two kids, and a dreamboat

wife–Saturdays would find him on the roof, painting

the hatch with red lead, or out front, rotating the tires

of the turquoise Biscayne, teaching me the criss-cross

pattern. I was soon condemned to tend the lawn, with

that infernal push-reel mower; while mom, squatting

on bare show-girl legs, pried out crabgrass with a

fork bladed tool. After chores, Frankie and me dared

each other to leap into the basement well, where just

below the edge hung the hose, coiled on its rack. An

errant loop caught my foot in mid air, slamming my

forehead against the edge of the concrete step beyond.

Frankie cried He’s dying, as blood drenched my

face. Mom dashed out the kitchen door, and met me

halfway up the wooden steps. Dad right behind her,

with her best tea towel, to staunch the flow. Then,

off to Dr. Lachman, who met us in his walk-up office,

to get the gash stitched up. Dad had seen his share

of blood, men in boats blasted apart, and the

maimed and wounded his ship ferried back from

Normandy He mortified a German prisoner, hooked

to an IV, telling him the fluid that trickled into his arm

was Juden’s blut. Then he showed the man his dog tag,

that labeled him as Hebrew. How he loved to tell that

story! Now we both had our scars–his, a whitish almond

shape imprinted on his buttock–from playing football in a

vacant lot in Brooklyn. Afraid of what his mom would say, he

asked the pharmacist to sew it up. And me, proud of the looks

I got for the bandage over my eye. We made a brotherhood

of blood. The scar lingers, a slanting crease among the

many horizontal furrows, plowed by time across my brow.